We replicate the journalistic article published by the newspaper El Ciudadano together with Fundación Tantí «The greenwashing of lithium mining: trying to hide the damage».

The extraction of this mineral is leaving traces that go beyond what is shown in corporate campaigns and the enormous publicity in the media. The consequences on the ecosystems and the social tissue of local communities highlight the contradictions of a controversial practice that some describe as greenwashing.

By Yasna Mussa

The worn iron gate is wide open. A red 4×4 truck parks in the background and two women install a banner with the SQM (Chemical and Mining Society of Chile) logo and the phrase “solutions for human development.” They announce that the workshop for women will begin shortly. At the place where the Tierra Viva space operates, a space that belongs to the Fundación del Agua (Water Foundation), the first participants have already begun to arrive and gather on a terrace and around the tables prepared for this instance.

Mining in this town seems to be inherent to the landscape. Wherever the eye lands there is a reminder: pollution, a wall with graffiti that says Ecocide, posters promoting foundations financed or created by mining companies, and mud-stained red trucks with company logos circulating everywhere.

–Here there is not only an environmental extractivism, but also a social, a cultural heritage, and a territorial one– the Licanantay farmer Rudecindo Espíndola bluntly utters.

In his comings and goings through the communities of San Pedro de Atacama, he has seen how the mining companies’ strategies work and the consequences they have on the communities. “They recruit two or three people from the towns and make or convert them into territorial operators. That is, political operators for the mining companies,” explains Espíndola.

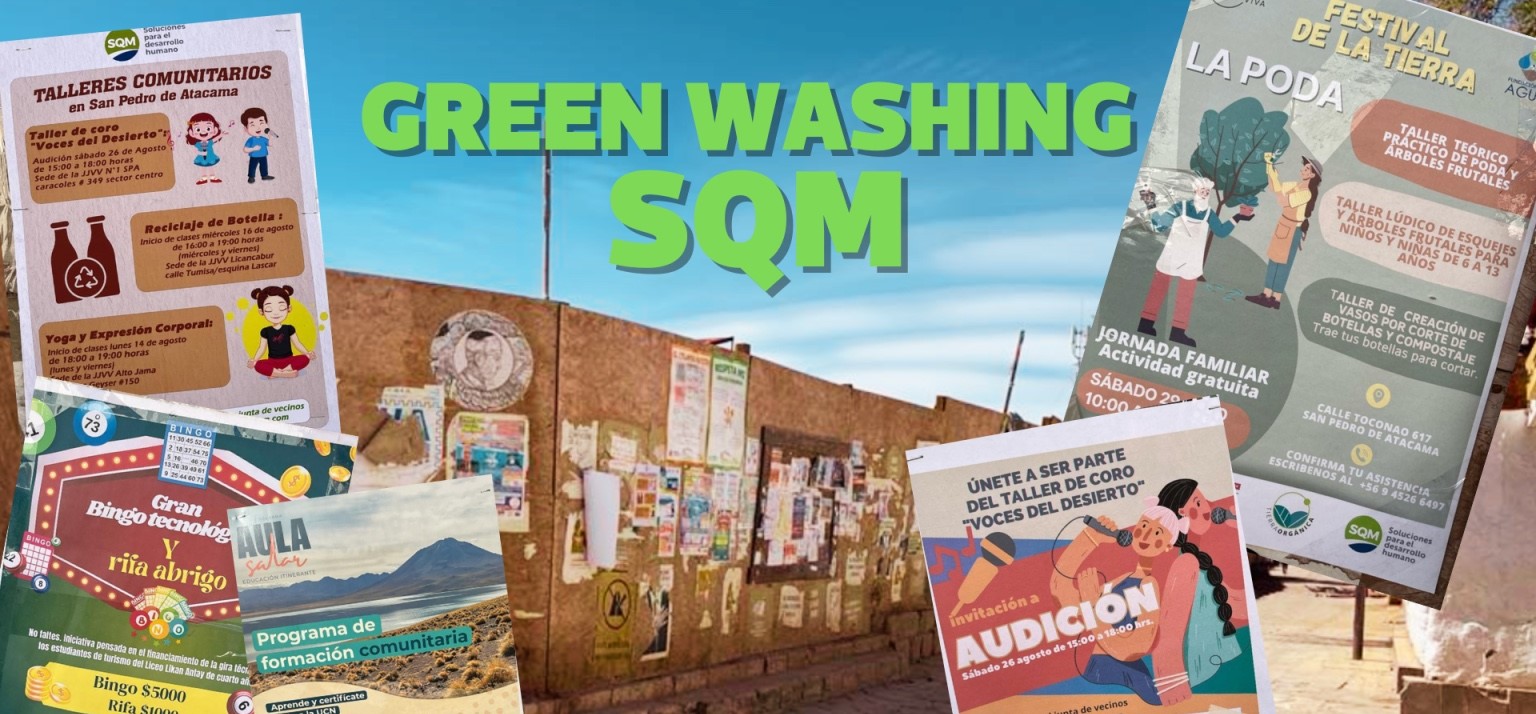

Community workshops on bottle recycling, yoga, and body expression. A remedial education program. A biennial of contemporary art. A community training program that invites you to learn about the hydrogeology of the Salar de Atacama basin; environmental monitoring techniques; water reuse techniques; hydroponic crops; sustainable agriculture; biodiversity in the Atacama Salt Flats; urban irrigation; water quality. These are all posters set up around the main square. On the lower side of each of these advertisements, the SQM logo appears in white, green, and blue. SQM is the company that has been exploiting the lithium reserves in the Salar de Atacama since 1993, and that according to an analysis carried out by Production Development Corporation (Corfo) , has been responsible, due to environmental violations, for the vegetation cover decrease on the east margin of the salt flat.

For Ingrid Garcés, a chemical civil engineer, PhD in Science, and an academic at the University of Antofagasta, this is a sensitive area of the salt flat that has been greatly impacted environmentally. The east side of the salt flat supports freshwater wetlands that cannot survive on brines, and that in turn allow for local biodiversity, including flora and fauna that depend on these wetlands to survive.

For this researcher who studies the salt flats, sustainable mining does not exist, since it is a contradiction to talk about caring for nature and at the same time extracting lithium on a large scale. “When we talk about sustainability we also talk about people not being abandoned. We have only extracted the mineral resource, but what is left in the soil and what they share with the communities is nothing,” says Garcés.

As demand for lithium grows, the impacts of mining “increasingly affect the communities where this harmful extraction takes place, endangering their access to water,” says a report made by Friends of the Earth.

For Espíndola and members of the local communities, SQM actions are greenwashing, defined as a green marketing practice aimed at creating an outward image of ecological responsibility. It is a term used to condemn companies that claim to care about the environment but whose practices demonstrate the opposite, because they actually pollute the planet.

The phenomenon is not new, but lithium-producing companies such as SQM have enhanced their relationships, contributions, and collaborations with local communities, in addition to increasing their presence in the media with million-dollar advertising campaigns that seek to disseminate this “green” social profile.

Broadcasted on television, during primetime, an emotional commercial shows a bird flying over the territory landing at different spots: first at a mobile dental clinic, then next to an elderly woman happily weaving during a workshop, on a sign that says Sustainability, and finally on an hydroponic garden. The voice-over says: “SQM equals experience, sustainability, innovation and technology.” A narrative repeated in advertising spaces on the radio, in newspapers, and in commercials that link lithium to mental health, although SQM has no relationship with this aspect of the mineral.

Media advertising is just one aspect of their campaign and corporate image. They also carry out permanent recreational activities and other more essential undertakings for the local communities’ daily life where the SQM banner has a constant presence.

–Here we perceive an increasing image-washing of mining companies, especially where the State is absent– says Rudecindo Espíndola.

He describes it in an image: a van that works as a dental clinic drives through the desert. It serves remote areas, distant places forgotten by State institutions, where getting sick or suffering from pain adds to the sorrow of living so far from healthcare institutions, in isolation. The van belongs to SQM and is the same one that appears in its television commercial.

SQM’s website states that the company’s motivations stem from a program that since 2019 has expanded its actions to sports and healthy living, as they assure that they detected “a special interest from the communities and an important commitment on behalf of the neighbors to participate in recreational activities and sports of various kinds”. In their program SQM proposes lines for community which, they claim, allow them to focus on relationship strategies and shared social values: Education and culture; social and productive development; historical heritage, and healthier life. Exactly the kinds of activities they describe on the posters spread throughout the city.

A vicious circle

The dependence of local communities on mining companies’ resources and aid is seen on a small scale, through, for example, donations to achieve specific goals such as study tours for highschool students. But it is also observed at a higher level: the municipality of San Pedro de Atacama has received more than 22 billion pesos in contributions from SQM and Albemarle, an American company and one of the largest lithium producers in the world. These contributions have been made in spite of the recommendations of the Contraloría, an administrative audit of the State of Chile, that has requested the municipalities to refrain from receiving donations from private companies.

Nicolás Villalobos is a sociologist working at the National Service for the Prevention and Rehabilitation of Drugs and Alcohol Consumption (Senda) through an agreement with the Municipality of San Pedro de Atacama. He has witnessed how mining companies are involved in donations for the development of community programs.

“We, as a program, suddenly do not have funds to carry out a campaign here and the issue of alcoholism is worrying. But we would never think of, for example, asking for money from mining companies. We are aware of what the exploitation process has been like and the consequences it has brought to the territory,” says Villalobos.

This sociologist exemplifies this with a recurring scene in San Pedro de Atacama: he was walking and suddenly saw that awnings with the SQM logo were all over the town square. They were promoting a talk about the environment, when at the same time “They are the ones who are drying up the Atacama salt flat basin and who are finally going to leave this entire area that we love so much, so damaged,” explains Villalobos.

“The mining companies strategically pry and fill in these cracks where the State does not have the capacity to aid people. And the State is not disgusted by this either,” says Villalobos. He has seen that on many occasions communities end up accepting help from the mining companies because they lack basic services such as electricity or a water well. But, though the money they receive from the companies solves material and infrastructural problems, at the same time it generates others: conflicts between neighbors, confrontations, betrayals, and inequality.

“All the communities, except two, are receiving money from mining companies. So the Municipality, the regional government, and everyone receives money from mining companies,” says Andrés Honorato, executive director of the Fundación del Agua. “When people from the communities tell you that they believe they are image-washing, they are also part of what is happening,” says Honorato. “Lithium’s worth is shared between the inhabitants of the territory, the company that operates the mining of the territory, and hopefully, it will reach the environment. Although this is the only concept that is not being directly defended by anyone. Communities talk about the environment but do not invest in it. None of the communities are using the money that the mining companies are giving to them, specifically SQM and Albemarle, to take care of it,” says Honorato. “They maintain that the State is not there for them. It is clearly not there, but they have lived their entire lives without the State. So now that there are resources, they are accepting them.”

–Mining, of course, is everywhere. And it is already a part of people’s mentality, as well,” says Valerie Silvestre, a neighbor and member of the San Pedro de Atacama Irrigators Association.

This mother of two young children explains what it means to live in a community so far from the big cities and where basic services are so limited. That is why she is not surprised that on a wall near the town square, a poster announces a study tour financed by a mining company. She, as an attorney, has witnessed these practices firsthand: where the State is not present, money from mining companies is always an option. If the school does not have the resources to take students to the beach at the end of the school year, about 400 km from San Pedro, mining companies or their respective foundations will likely be asked to collaborate.

SQM assures on its website that the programs it carries out “are promoted by the company under our four lines of action to engage with the community. We execute these actions along with our neighbors, with whom we keep a direct relationship based on trust.”

Rudecindo Espíndola sees reality very differently from how SQM defines it. “There has been violence between residents who defend SQM and others who are in a different position concerning the massive extraction of water, due to an environmental, cultural, and community issue,” says Espíndola. “Deep down, some communities are accepting that the mining companies are fulfilling the role of an absent State. The closest thing we have is the Municipality, but it does not shine, it is not there, it only does basic and minimal things.”